Massimo Introvigne

The launch of Bitter Winter has been greeted by a good media coverage, and has been covered with sympathy by several human rights and academic blogs and websites, from France to Australia. We did expect different reactions, too. One day after the launch,Google advised the editor of Bitter Winter that a “foreign government” was persistently trying to hack his personal email. And, even before we sent out our first newsletter, McAfee and other anti-spam services were bombarded by reports by “independent consumers” denouncing our activities as spam. These were minor annoyances, whose source was easily detected. Having crossed swords in the past with the Russians, who are at least highly professional, I would say that in this case we had to do with amateurs.

The launch of Bitter Winter has been greeted by a good media coverage, and has been covered with sympathy by several human rights and academic blogs and websites, from France to Australia. We did expect different reactions, too. One day after the launch,Google advised the editor of Bitter Winter that a “foreign government” was persistently trying to hack his personal email. And, even before we sent out our first newsletter, McAfee and other anti-spam services were bombarded by reports by “independent consumers” denouncing our activities as spam. These were minor annoyances, whose source was easily detected. Having crossed swords in the past with the Russians, who are at least highly professional, I would say that in this case we had to do with amateurs.

More interesting was an article in Vatican Insider, the supplement on religion of the Italian daily newspaper La Stampa. I would like to clarify that I regard Vatican Insider as one of the best sources of news about the Catholic Church in the world. In fact, Vatican Insider covered sympathetically the launch of Bitter Winter. However, an article by Gianni Valente went in a different direction.

Valente is a personal friend of the present Pope, and a respected journalist in several fields. He doesn’t seem, however, to be well-informed about Chinese new religious movements, an area of which I am an expert. In 2013, he hailed as “an in-depth study” of the largest Chinese Christian new religious movement, The Church of Almighty God, a short article by Father Vito Del Prete published by the Vatican news agency Fides, a digest of Western and Chinese newspaper articles that ignored the academic literature, including the one by Chinese Communist scholars, to its peril. In fact, Del Prete’s article included gross factual mistakes. It dated the foundation of The Church of Almighty God to 1989 in Heilongjang rather than 1991 in Henan, believed that the name of the Chinese woman it recognizes as Almighty God was “Deng,” a name used only in anti-cult propaganda, insisted that the members of the Church were mostly ignorant peasants (a theory no scholar who has interviewed a certain amount of them would confirm) and that “many” are converts from Catholicism (in fact, most come from Protestant House Churches), and regarded Zhao Weishan as the only “founder” of the movement, an idea that betrays the misogynism of Chinese propaganda, which could not admit that a woman had founded a large and phenomenally successful religious organization. In fact the founder of The Church of Almighty God is the(female) person it recognizes as Almighty God.

Worse, Del Prete accepted from the same propaganda the idea that The Church of Almighty God kills its members if they want to leave “the cult.” This is one of the most egregious examples of fake news spread by the Chinese regime to justify its persecution of The Church of Almighty God. I was invited twice in 2017 by the Chinese Anti-xie–jiao Association to conferences organized in China against The Church of Almighty God. They were covered by Chinese official media, and were attended by high officers of the police unit specialized in fighting The Church of Almighty God. Requested to produce evidence of the violence, including homicides, allegedly perpetrated by the Church against those who want to leave, or have left, its fold, the police officers answered that no hard evidence exists but there are “rumors.”

I mention all this because in his 2018 article Valente came back to what he wrote in 2013 and mentioned again Del Prete, as if from 2013 to 2018 scholars had not produced a substantial literature on The Church of Almighty God, making these theories untenable.

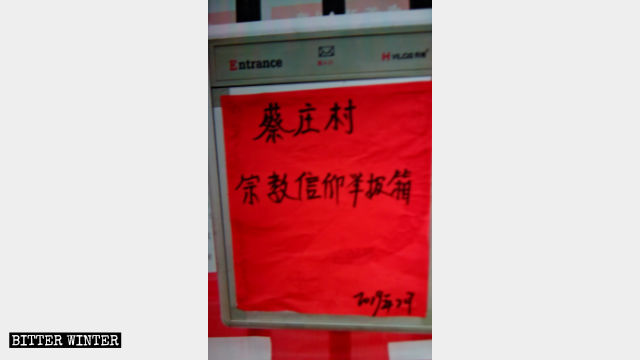

However, the main purpose of Valente’s article is not to defame The Church of Almighty God, although he does so as a matter of course. What he really wants to attack are consistent news “reported by local—often anonymous—witnesses” about police and CCP harassment of Catholics in Henan. Valente does not mention Bitter Winter explicitly, but we are among the few (together with ChinaAid and AsiaNews) that published daily news from Henan about attacks against Catholic churches and congregations there. News were obviously anonymous: the brave observers who report to us what is happening (and take pictures that we publish), if identified, would go to jail or worse.

Perhaps, Valente suggests, these reports are true, but one has to consider the peculiar situation of Henan, where both House Churches including The Church of Almighty God, which he believes are financed and perhaps created by American neo-conservatives, if not directly by the CIA, conspire to overthrow the Communist regime. Trying to make China more democratic would be a worthy enterprise, and the CIA should be applauded for this, but the idea that American institutions finance The Church of Almighty God is ridiculous, although it is both true and not surprising that American Evangelicals (who are obviously not part of the CIA) support certain Chinese Evangelical churches. The largest House Churches, however, are genuine and original Chinese creations.

Valente applies to China the discredited “Rockefeller theory” that was popular in Latin America in the 20th century. In some Latin American countries, the Catholic Church was politically liberal, and some of its liberation theologians were openly Marxist. Dissatisfied with these positions, many Catholics voted with their feet and joined the fast-growing Pentecostal churches. Liberation theologians argued that Pentecostals were successful because they were financed by the Rockefeller Foundation and other fronts for American imperialism. The theory was consistently laughed at by academic scholars of Latin American Pentecostalism. Finally, as the 20th century ended, voices were heard even in the liberation theology camp admitting that the analysis was wrong and that the most successful Pentecostal denominations in Latin America were indigenous and not significantly financed by U.S. agencies, some of them being in fact anti-American.

The dead horse of the “Rockefeller theory” is now revived by Valente and applied to China in the shape of a bizarre conspiracy theory. Valente is an intelligent journalist, and does not do it by chance. As Father Bernardo Cervellera, the best Catholic expert of China, explained in an interview to Bitter Winter, which probably also disturbed Valente, there is in the Catholic Church a faction insisting for a quick agreement with the CCP. At one stage, Cervellera explained, this faction started spreading fake news about an imminent signature of the agreement in order to put pressure on the CCP, and overcome the resistances that do exist within the Party as well. The CCP cares very much about its image abroad. Attempts to buy academics to support its persecution of the House Churches and the xie jiao failed. Now Valente tells Beijing that, should the agreement be signed, the public relation problem might be solved. Vatican-connected journalists would be ready to justify the persecution by claiming that the persecuted are agents of the American imperialism.

Of course, this runs counter the teachings by Vatican II and of Valente’s own personal friend, Pope Francis, that religious liberty is indivisible and Catholics should protest when the freedom of anyreligion is threatened, not just theirs. Paris may have been worth a Mass once, but Beijing is not worth betraying millions of Christians arrested, tortured, and killed.

As I have stated elsewhere, I do not agree with those arch-conservative Catholics who use the negotiations with China in order to attack Pope Francis. They forget that these negotiations had been started by the previous Pope, Benedict XVI. And I do not share the opinion that anynegotiation by the Catholic Church with the Chinese regime is wrong and immoral. The Holy See is a political as well as a religious entity, and has a tradition of negotiating with pretty much everybody. The problem is the content of the negotiation. Negotiating with Beijing is like the proverbial supping with the Devil. You can do it, but you need a very long spoon. Dipping its spoon in the poison of Chinese propaganda against other religions would put the Catholic Church in a very difficult and ambitious position.

Soure: BITTER WINTER / Massimo Introvigne