Hong Kong scholar Edward Irons explains the historical roots of the proscription of certain groups as xie jiao (heterodox teachings), and how being on the list of the xie jiao means being a main target for persecution.

Massimo Introvigne

Edward Irons is a well-known Hong-Kong-based researcher, consultant, and writer on Chinese culture and religion. He specializes in Yiguandao and other Chinese new religions, as well as leadership studies. He obtained his PhD from the Graduate Theological Union in 2000. He is the Director of the Hong Kong Institute for Culture, Commerce and Religion, which he founded in 2003.

Irons has studied in depth the repression of certain religious groups in Nationalist and Communist China, persecuted as “cults” or “heterodox teachings” (xie jiao). These notions are not always clear, even for scholars, and we have asked Dr. Irons to help us clarify them.

We know that “heterodox” groups were repressed in Imperial China and that the expression xie jiao originated in the Ming era. But today we will not go so far, and start from the crackdown on certain religions in Nationalist China in the 1930s. This may come as a surprise to some, as the Nationalists after all were not the Communists, and were not officially atheistic. Which groups were persecuted and why?

What happened in the 1930s serves as background to developments under the People’s Republic. We can even go further back, to the late-Qing period, to find the origin of anti-religious sentiment. Anti-superstition and anti-tradition were growing intellectual trends among most educated Chinese beginning in the late Qing, roughly the last half of the 19th century. The version of modernity promoted by many intellectuals left no room for popular religious practices like spirit writing or cultic worship. The Kuomintang (KMT), which came to power in 1927, offered something else, an ideology of rationality. In addition, organized religions such as Buddhism were widely perceived as being backward, inhibiting China’s transformation into a modern nation. Temples held large parcels of land, which was seen as unfair. And monks were seen as being low-educated and not sincere in religious practice. Article 6 of the Republican constitution guaranteed “freedom of belief.” At the same time the government also maintained a strict separation of church and state.

So between 1927 and 1931 the Republican government launched a formal campaign against superstition and institutional religion. The government waged consistent warfare against Buddhism in particular. There was sporadic but widespread confiscation of the property of Buddhist and local deity temples. This campaign is best seen as an outgrowth of the powerful nationalistic movement dating from 1919. This movement desired for China to become modern. There was strong sentiment against tradition and superstition. The KMT translated this attitude of anti-superstition into policy, as would the People’s Republic after 1949. The campaign against superstition only ended when, in 1934, KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石, Jiang Jieshi, 1897–1975) launched his own spiritual program, the New Life Movement (新生活運動, xinshenghuo yundong).

The Nationalist government focus was mainly on established Buddhism. Ironically, many new organized religious groups rose up during the 1920s and 1930s. Some were Buddhist, some Daoist, and some Christian. I don’t think any of these were prominent enough to cause concern in the Nationalist government, except for one, Yiguandao.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rose to power and there was in the 1950s another massive crackdown on certain religious groups, targeting in particular Yiguandao, a very successful non-Christian new religious movement, millions of members of which were arrested. Why Yiguandao? Can you tell us what happened?

Yiguandao is a Chinese syncretic religion. First established in its modern form in the 1930s, it has deep roots in Chinese popular belief systems. According to some sources, in 1947 it had grown to twelve million members. Yiguandao was outlawed and actively suppressed as part of the Anti-Heterodox Groups and Secret Societies Movement (fandong huidaomen 反动会道门) of 1951–1953. Other groups were suppressed as well, but it appears that Yiguandao was the main target. Millions of devotees were arrested. Yiguandao leaders were thrown into prison and from some accounts killed outright. Within a few years, Yiguandao was extinguished as a religious network in Mainland China, and it remained only as a faint cultural memory from the 1930s and 1940s. It is still active in Taiwan, divided into various branches, with some 800,000 followers. Yiguandao temples and temple networks are also found in Hong Kong, Korea, and Japan; throughout Southeast Asia; and in most countries of Europe and North America.

Why was Yiguandao so severely persecuted? Marxist ideological antagonism toward religion in general is well known. In addition, religious leaders were often personally associated with the ruling classes. In Yiguandao’s case, the movement had grown rapidly throughout the war against Japan, especially in areas of China under Japanese occupation. This rapid growth caused people to wonder if the group had a special relationship with the puppet regime propped up by the Japanese. Immediately after Japan’s surrender, there were rumors of collusion. So Yiguandao was not only a large, well-organized religious group, it was seen as being unpatriotic.

The situation of course changed with the Cultural Revolution, when all religions were persecuted. And then, it changed again…

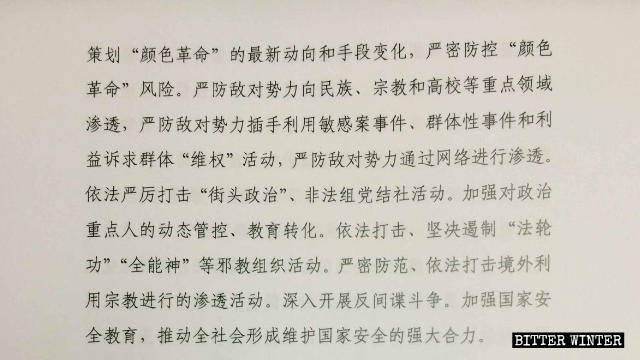

The early 1960s was a period of overt antagonism to all forms of religion. This hostility relaxed with the economic reforms introduced from 1979. But religion was not a topic that could be overlooked. Religious shocks such as the Falun Gong demonstrations in 1999 and the rapid rise in non-official Christianity in the countryside posed challenges to the government. From the 1990s, the state chose to target specific religious groups. These groups have been prominently declared illegal and suppressed by the various security bureaus. This targeted approach differed from the 1950s and 60s, in which the government made broad proscriptions focused on “religion” as a category of thought and action that was harmful or false. The new focus moved to specific groups that were deemed to be harmful and thus illegal. Of course, individual groups inside China had already been proscribed, starting with the “Shouters” in 1983.

How did the singling out of certain groups as xie jiao started?

Following the Falun Gong incident of 1999, the Public Security Bureau established a new organ, the Public Security Anti-Xie Jiao Organization (公安部反邪教组, gonganbu fanxie jiao zu), called informally “the 610 Office,” to focus on xie jiao groups. In November of 2000, another organization was established, the China Anti-Xie Jiao Association, commonly known in English as “the China Anti-Cult Association” (中国反邪教协会, zhongguo fanxie jiao xiehui, abbreviated as CACA). A distinction should be made between such government offices, which may use the term “anti-cult” in their English translations, and overseas civil society groups dedicated to fighting “cults.” The Chinese institutions in fact are all anti-xie jiao. Officially, CACA is a voluntary, non-profit organization. In practice, the media appears to treat its announcements, for instance the June 4, 2014 front-page article on xie jiao groups, as official government notices.

You have studied extensively the Chinese lists of xie jiao. How did these lists come to be established?

Since the mid-1990s, illegal and banned groups have been categorized and controlled through designation as xie jiao. At some point in the 1990s, a specific list of exactly which groups are categorized as xie jiao was compiled. This list has generated great interest in the international media. The first extensive compilation included overseas groups such as the Branch Davidians and Aum Shinrikyo. In this initial version, the focus was on potentially dangerous overseas groups; xie jiao became analogous to the term “cult” as used in other countries. But in 1995, the list was expanded to designate groups deemed to be not only dangerous but also heretical. Heretical here means not following doctrine of the five officially sanctioned religious bodies in China—Protestantism (the Three-Self Church), Catholicism, Buddhism, Daoism, and Islam. Many of the unsanctioned groups were homegrown and had evolved out of the Protestant traditions; only one group on the initial list, Supreme Master Ching Hai, was based outside Mainland China. Later that year, the list was expanded by the inclusion of more local Protestant groups and such overseas groups as the Children of God (the Family) and the Unification Church. The Falun Gong incident of 1999, in which thousands of followers surrounded the senior leaders’ compound in Beijing, spurred the government’s thinking on xie jiao. For the first time a well-organized group, one that had been nurtured through government support, was seen as a threat to China and, more seriously, to the CCP. The Ministry of Public Security in 1998 designated Falun Gong as a xie jiao. As if to clarify the implication, xie jiao organizations were formally made illegal by a legislative resolution in 1999. It was at this time that the “610” anti-cult unit was established. The State Council in 2000 followed this up by establishing a separate network of offices to deal with xie jiao. The government had published the updated list of eighteen xie jiao in 1995. The Shouters and The Church of Almighty God were included.

What about the current list?

On September 18, 2017, the revamped China Anti-Cult (xie jiao) website reiterated the list of banned groups which had been listed publicly in 2014. Of the total 20 groups, eleven were listed as being “dangerous:” 1. Falun Gong (法轮功) 2. The Church of Almighty God (全能神) 3. The Shouters (呼喊派) 4. The Disciples Society (⻔门徒会) 5. Unification Church (统⼀一教) 6. Guanyin Method (观⾳音法⻔门) 7. Bloody Holy Spirit (⾎血⽔水圣灵) 8. Full Scope Church (全范围教会) 9. Three Grades of Servants (三班仆⼈人派) 10. True Buddha School (灵仙真佛宗) 11. Mainland China Administrative Deacon Station (中华⼤大陆⾏行行政执事站). In addition, the website warned the public to “be on guard against” an additional nine groups: the Lingling Church, the Anointed King, the Children of God, Dami Mission, the New Testament Church, the World Elijah Gospel Mission Society, the Lord God Sect, the Yuandun Dharma Gate, and the South China Church. From this list it appears there are two categories of groups, eleven major (“dangerous”) groups, and nine others, for a total of 20.

What are the consequences of being included in the list?

Inclusion on the list means the group is not seen as a “religion,” but simply as an illegal organization. So this list has had an immense influence on the perception of new religions. Being on the list means the full weight of state coercion can be applied against any individual associated with any of the groups on the list. Article 300 of the Chinese Criminal Code makes “using,” i.e. being active in a xie jiao, a crime punishable by three to seven years of imprisonment “or more.” This level of severity echoes the nearly absolute suppression of Yiguandao and other religious groups in the 1950s. For Falun Gong, as with Yiguandao before it, the only way to survive was to move overseas, away from the direct influence of the Chinese state. Being seen as an illegal entity forces many groups members to “go underground.” Finally, the xie jiao list also acts as the conceptual opposite pole to allowed religions. As a result, any group not belonging to one end of the spectrum or another is cast into a limbo of uncertainty. Some religious groups have scurried to head off the threat of inclusion on the xie jiao list. Overseas religions, including the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and Scientology, have initiated discussions with the Chinese government to explain their peaceful intentions. Finally, these lists, publicized so widely, have given scholars a valuable window on official policy regarding what counts as acceptable religious behavior, and what is suppressed and persecuted.

Source:BITTER WINTER/Massimo Introvigne