“Official” or “government-controlled” religions are often mentioned in China. Five religious bodies are indeed authorized by the regime, although even their liberty is limited.

Bitter Winter readers often encounter news about “government-controlled” religions, which are allowed to operate in China by the regime. What are they, exactly? And are they really free?

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regards atheism as part of its fundamental doctrines. Atheism is declared in many official documents an essential and irreformable part of CCP ideology. However, when the CCP came to power in 1949, it was a fact of life that China was full of religions. Mao Zedong (1893–1976) believed that religion would be eradicated in China by extirpating its social roots, i.e. by making China a truly Communist country. In the meantime, religions, rather than uprooted immediately and violently, should be quietly accompanied to their demise by controlling them, in order to prevent any religious uprising or counter-revolution.

Chairman Mao ordered the expulsion of all foreign missionaries, the arrest or execution of all religious leaders whose opposition to the regime was known, and the formation of religious bodies strictly controlled by the CCP. The leaders of these bodies should be appointed by the CCP and forbidden to keep any contact with foreign or international religious organizations.

As much as the CCP wanted to humor Chairman Mao, the task proved very difficult. In order to be believable, the new religious bodies should include at least some existing religious leaders, and few of them accepted to be recruited by the CCP. After a complicated process of threats and blandishments, finally the CCP was able between 1954 and 1957 to establish five government-controlled religious bodies:

- The China Protestant Three Self Patriotic Movement, in short Three Self Church (1954), a unified body including all Protestants loyal to the CCP, characterized by the “three self,” i.e. “self-administration, self-support, and self-propagation,” by which the CCP meant that no help should be received or accepted from foreign missionaries and international bodies;

- The China Buddhist Association (1957);

- The China Islamic Association (1957);

- The China Taoist Association (1957);

- The China Catholic Laity Patriotic Committee (1957), later renamed China Catholic Patriotic Committee, in short the Patriotic Catholic Church.

It was, of course, hardly believable that the immense richness and theological variety of Chinese Protestant Christianity could be reduced to one single church. And the Vatican promptly declared the Patriotic Catholic Church, whose bishops were appointed by the CCP rather than by Rome, schismatic and not Catholic at all. The Catholics loyal to Rome went underground and established a vibrant Underground Catholic Church, although most of their bishops were arrested, and many died in jail.

The five official bodies were never popular. However, gathering all the Chinese still regarding themselves as religious in one of the five officially recognized bodies was a task entrusted to the police more than to the theologians.

The five bodies were initially active for a decade only. In 1966, the Cultural Revolution started. It persecuted with equal ferocity both authorized and unauthorized religion. Almost all places of worship were destroyed or converted into barracks or stables. Cultural treasures were lost forever, as statues were smashed and books burned. Thousands of pastors, priests, monks and imams were killed, and no form of worship or belief was tolerated.

When the dust of the Cultural Revolution finally settled, Chairman Mao died (in 1976), and Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997) rose to power (in 1978), the CCP discovered, to its surprise, that religion had not disappeared, notwithstanding one of the worst persecutions in human history. Only, it went more deeply underground. This led Deng to revise the ideas of Mao about religion. He did not proclaim them wrong, but adopted a different timeline, as he believed that the demise of religion may require centuries, rather than mere decades, of Communist rule in China.

In 1982, Deng ordered the publication of a text known as “The Basic Viewpoint and Policy on the Religious Affairs during the Socialist Period of Our Country,” later known as “Document No. 19.” The five government-controlled bodies were restored to their early position, although limitations to religious activities were also reiterated, and Deng insisted that propaganda for atheism should continue to be carried out.

In fact, the five bodies never controlled all religious activity. As sociologist Fenggang Yang wrote in 2006, the CCP had created a “red market” of approved religion. Sociological theory, however, maintain that not even totalitarian regimes are able to fully control religion. A “grey market” outside the five approved bodies existed before 1982 and continued to exist after. There are also ambiguous areas. One was Qi Gong, a set of exercises for body training and meditation of Buddhist and Taoist origins. The CCP promoted the groups organizing the practice of Qi Gong as part of traditional Chinese culture and medicine rather than religion, although many of them obviously included in their teachings religious elements. However, when one of these groups, Falun Gong, grew so much that it was perceived as a threat by the CCP, the Party started a campaign for eradicating it and revived the old Imperial practice of promulgating lists of xie jiao, “heterodox teachings,” which were presented as a social danger of great magnitude and should be “eradicated like tumors.” Several other groups were added to the list of xie jiao, and mercilessly hunted.

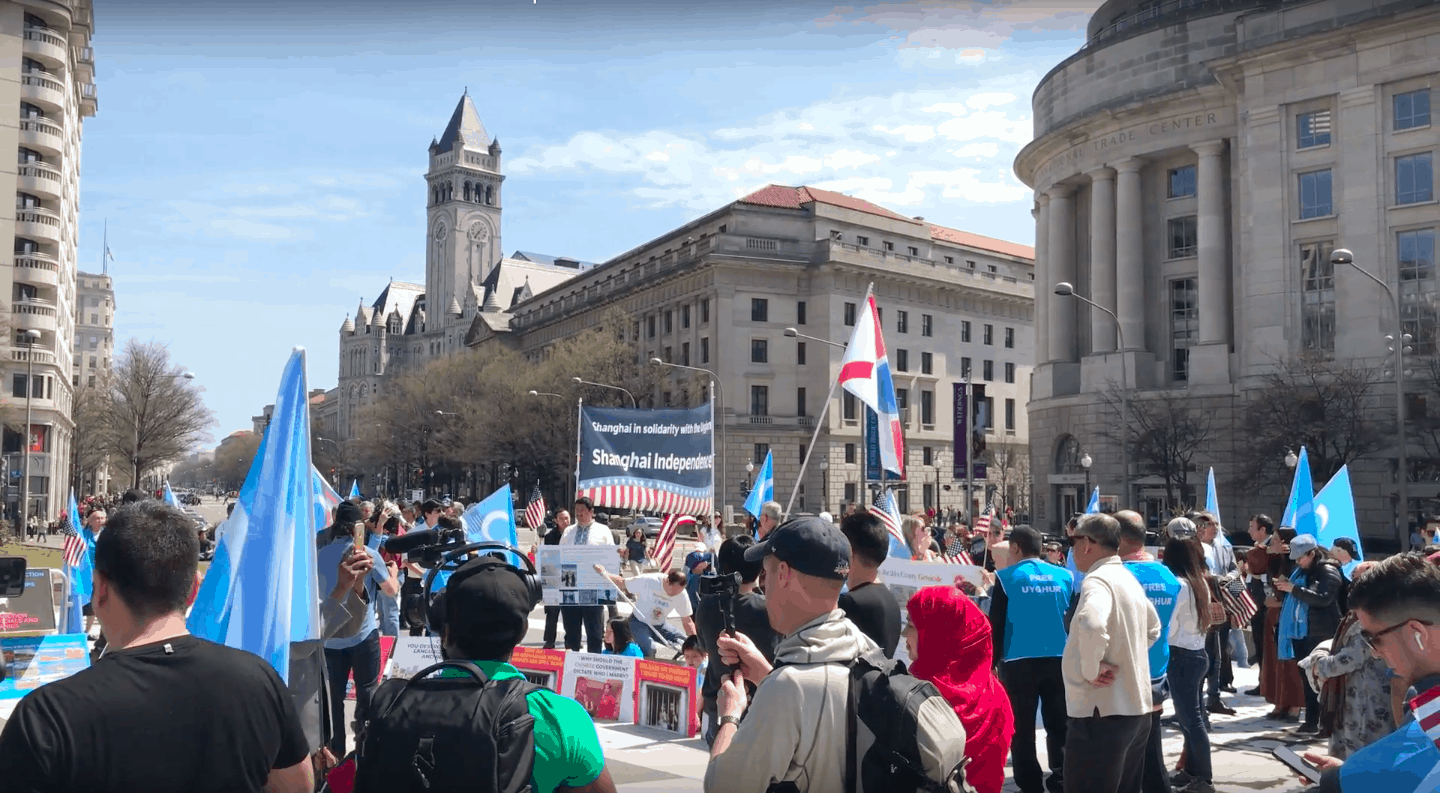

In the terms of Fenggang Yang, at least in the official narrative of the regime, the five approved bodies were the virtuous “red market” of religion, and the xie jiao were its evil “black market.” This was only part of the story. The “grey market” continued to exist, and was indeed the largest segment of religion in China. It included the Underground Catholic Church, Protestant House Churches (as not all of them were listed as xie jiao), which resisted efforts to join the Three Self Movement, Buddhist and Taoist temples that remained outside the official Buddhist an Taoist associations, and Muslims (particularly, but not exclusively, in Xinjiang) who regarded the China Islamic Association as an instrument to slowly eradicate Islam altogether. How the regime reacted and reacts to the existence of the “grey market” will be discussed by Bitter Winter in future articles.

But what about the “red market”? When Chinese propaganda assures us that religion in China is free and even supported by the CCP money, it refers to the five government-controlled bodies. Indeed, the lavish lifestyle of the leaders of these bodies seems to confirm that at least the part of the propaganda about money is not false.

However, the activity of the religious organizations belonging to the five bodies is by no means free. First, obviously, no criticism of the CCP is allowed. Second, proselytization is forbidden and preaching is allowed only within the authorized places of worship. When Russia with the Yarovaya Laws passed similar anti-proselytization measures in 2016, there was an international outcry, but few realized that China had always been in the same situation.

Third, there are a number of fastidious administrative regulations, placing in fact the authorized religious communities at the mercy of the local CCP authorities. It does not take much to find that one of these rules has been breached, and the consequences may be very serious, up to the dynamiting of the places of worship and the arrest of the clergy. The most odious regulation is the one practically equating religion to pornography, and mandating that no minor of 18 can enter a place of worship or participate in any kind of religious activities. After the reform of religious regulations of 2018, it is enforced with great rigidity. Churches have been shut down simply because mothers entered them with their infant children in their arms.

Two final remarks. The “red market” was established originally to prevent the presence in China of religious bodies with international connections. These connections are still forbidden, but the five official organizations are expected to support the Chinese propaganda by wining and dining foreign visitors, trying to persuade them that religion is free in China. They are also expected to support the persecution of xie jiao by supplying theological arguments confirming that their teachings are heretic.

Second, we do not want to give the impression that all believers who participate in the activities of the “red market” religion are insincere, or that the “official” religion only exists for the purpose of propaganda. This may be the case in specific areas, but is not the rule. There are places in China where the “red market” offers the only opportunity of keeping some contact with religion. Sincere believers may decide that taking advantage of this opportunity is, after all, better than nothing.

Source: Bitter Winter